Additional essays in this series:

Kelly Starlings Lyon: How Do Women Use Art As Resistance?

Traci Sorrell: Why Do You Speak Out?

Justina Ireland: There is A Minefield and You Will Become a Demolitions Expert

Ambelin Kwaymullina: On Being Loud and Hopeful

Cheryl Willis Hudson: Women Lead the Independent Publishing Movement

Laura Jiménez: Static Bodies in Motion: Representations of Girls in Graphic Novels

Sonia Alejandra Rodriguez: Don’t Call Me Strong

Maya Gonzalez: What Do I Speak Out? True Power Rises

Sujei Lugo: When Women Speak

Neesha Meminger: I Want to Talk About Power

A couple of weeks ago, I had the pleasure of presenting with Dr. Laura Jiménez and Dr. Sarah Park Dahlen at the Center for Teaching Through Children’s Books in Skokie, IL. I don’t believe there are recordings of the day’s events, didn’t take notes while on the panel but, I do remember a brief discussion about our ‘anger’, something to the effect of its appropriateness. Afterwards, one of us was even told that perhaps she might be heard if she weren’t quite so angry. I ascertain that even in this age of all things positive, anger still remains a necessary and human reaction to hurt, injustice, pain or fear. Anger is positive when it motivates us to action. While we’re given the stereotypical perception of screaming, out of control angry women, there are those who through their wisdom, knowledge, determination and indissoluble resolve are able to seethe in a manner that allows for nothing less than forward motion. They get it done and they never raise their voice. Zetta Elliott is one such person. For her, “Nice is Not Enough”.

Zetta continues upon the thoughts presented in a conversation on her own blog with author Laura Atkins. It can be found here.

“Nice Is Not Enough”

An older colleague once jokingly described the children’s literature community as “the bunny-eat-bunny world of kid lit.” That phrase stayed with me not because I found it amusing, but because replacing “dog” with “bunny” says so much about the way many in the kid lit community see themselves—not as fierce predators or ruthless competitors, but as harmless creatures operating with innocent intent.

I believe this kindly self-image partly explains the stunned and defensive reaction when accusations of racism arise within the children’s literature arena. The recent controversy over a mural at the Dr. Seuss Museum in Springfield, MA demonstrates the well-worn dynamic that plays out over and over again: concerns are raised (most often by people of color or Indigenous folks) and defenders of the problematic image/text/act (most often White) respond with shock, indignation, and counter-accusations of censorship made with a degree of hostility one wouldn’t expect from gentle “bunnies.”

That so many kid lit creators feel the need to cultivate and preserve this image is telling. Last summer an article in Publishers Weekly speculated on a world ruled by children’s authors. Deborah Underwood, a White female author, explained that she penned the “love letter” because “those in power seem to be missing some important qualities—qualities that children’s authors and illustrators have in abundance.” Underwood then listed thirteen complimentary traits that would make her peers better suited to lead the country. I almost stopped reading at #4: “We understand the importance of diversity.”

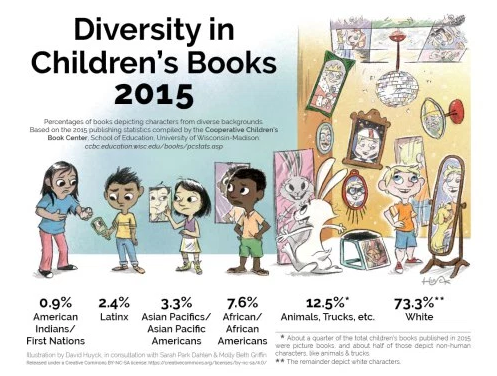

I wanted to remind Ms. Underwood that 53% of White women voters helped to elect the current president. White women dominate the publishing industry in the US, as well as the fields of education and library science; they make up the majority of literary agents and booksellers. White authors and illustrators were responsible for 88% of the books produced for young readers last year despite making up 61% of the population. The bunny in this graphic commissioned by Prof. Sarah Park Dahlen with data supplied by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center reminds us that in 2015, there were almost as many books about animals and inanimate objects as there were about kids of color and Native children. And, of course, the overwhelming majority of books featured White kids.

When I show this graphic to students during school visits, we don’t talk about how White supremacy ensures that one child is unfairly advantaged at the expense of the others. Instead I ask them to tell me what they see, and the students describe the room full of mirrors where the White child gets to envision himself in every possible heroic role. “Is that fair?” I ask them, and they always respond with a resounding “No!” If social justice isn’t at the center of the children’s literature community, why would anyone assume that kid lit creators would preside over a more just world?

You could only make that leap if you truly believed that simply acting nice makes you morally superior and fit to rule. But many of us know all too well that public displays of niceness often serve to camouflage or deflect attention away from actions and policies that are anything but kind. In a 2016 essay, Elle Dowd admits that “[Whites] say we value niceness, but what we really value is being in charge of what that looks like and when it’s appropriate, by our own standards.” As we’ve seen with the Black Lives Matter movement and NFL protestors, members of marginalized groups are expected to be civil, grateful, and not angry, never disrupting the comfort of the dominant group. Yet Dowd reminds us that niceness has a “dangerous relationship to power” and almost always “finds a way to center itself on white ideals, white experiences, white feelings.”

I am not known for being nice—and I’m okay with that. For close to a decade I’ve been advocating for greater equity and diversity within the children’s publishing industry. I’ve written countless essays and given public talks in the US and abroad—to no avail. I’ve been called a troublemaker since I was a child, and I can’t even remember how old I was the first time a White adult chastised me for having a “bad attitude.” Defiance is not tolerated in Black girls, and many of us reach womanhood knowing that intelligence coupled with assertiveness will almost always be read—and dismissed—as irrational rage. My particular Black feminist perspective isn’t much valued within the kid lit community partly because I refuse to “play nice.” My first picture book won a number of awards when it was published in 2008, but no editors or agents expressed interest in my thirty other manuscripts. When I used my scholarly training to investigate, I discovered the problem wasn’t personal but institutional; it wasn’t my “bad attitude,” it was racism. Left with no other options, I self-published over twenty books only to face the disdain or pity of those committed to a system that’s clearly rigged.

As an immigrant, I’m still expected to be thankful for the opportunities I’ve been given and I do feel lucky to live in a country where conversations about race are open and ongoing (if not always productive). I grew up in Canada and so I know the conceit of civility all too well. I learned early on to be soft-spoken and polite, to mind my manners and never litter. I skipped a grade and was eager to earn the approval of my White teachers, but by the time I reached high school, I was no longer willing to remain silent about the exclusion of Blacks from the curriculum. My maternal grandmother (who presented as White but identified as “Negro”) kept a framed excerpt of Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream Speech” on the wall and regularly reminded me that our African American ancestors left Philadelphia in the 1830s seeking freedom in the Great White North. They soon discovered there was no way to be free and Black in Canada, however, and so they attempted to merge into Whiteness through intermarriage. My mother spoiled that plan by wedding an Afro-Caribbean man in 1967, and when my father gave up on Canada and moved to the US, I followed. He warned me not to attend rallies with my activist friends in Brooklyn, but I’d had a “safe” life in Canada. I was ready to fight for something more.

Moving to the US, starting graduate school at NYU, and living in a majority-Black neighborhood for the first time accelerated the process of decolonizing my imagination. I immersed myself in African American literature, and worked hard to silence the echo of Dickens I could hear in my own writing. I revisited the books I loved as a child and was saddened to find that most were racist, sexist, imperialist, and problematic in other ways. The authors I once revered—all White, mostly British—lost their shine but not their place on my bookshelf. Theodore Geisel’s racism is disappointing but not particularly surprising; Seuss scholar Phil Nel offers this useful analogy to which many of us can relate: “Seuss is the well-intentioned white activist who isn’t as ‘woke’ as [s]he thinks [s]he is.” The Little Island by Margaret Wise Brown was a favorite picture book of mine and currently helps me map my family’s migrations between archipelagoes. Yet it was disturbing to learn that Brown had insisted another one of her books be covered in real fur—a demand that resulted in the slaughter of thousands of rabbits. I did send my nieces a copy of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden despite its issues, but would never share Tintin comics with them. Both girls are obsessed with graphic novels and can read in French, so Marguerite Abouet’s Aya series is a better choice.

I can’t shield my nieces from the racism they’re likely to encounter in the world, but I can try to spare them the traumatic effects of consuming—as I did—a diet of books that erase or distort Black people. When I was just a few years older than they are now, I wrote a story populated with characters who looked nothing like me or my family. I’d never read any fantasy fiction with Black kids at the center, and so erased myself in order to reproduce the White heroines of my favorite novels. My nieces are growing up in the era of #BlackGirlMagic but that doesn’t mean they’re immune to images of smiling slaves and offensive stereotypes in books that nonetheless rack up starred reviews (not a surprise since almost 90% of reviewers are White women, according to the 2015 Lee & Low Diversity Baseline Survey,).

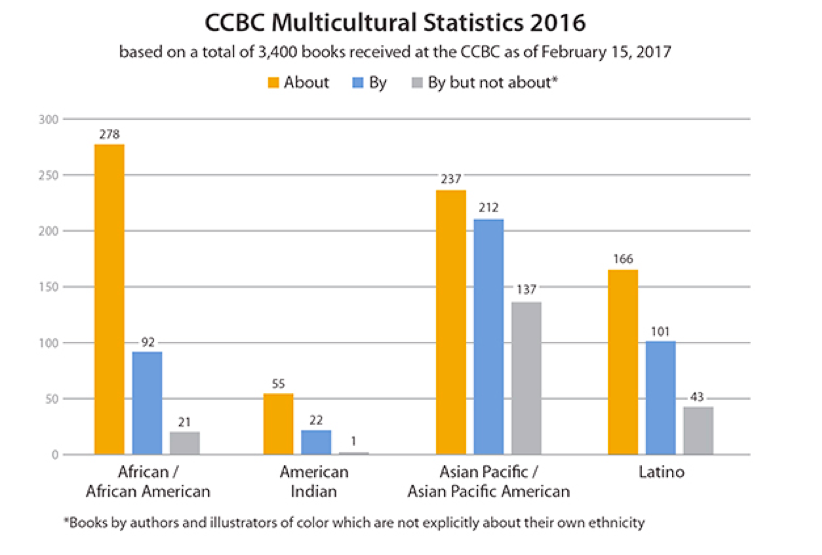

Elsewhere I have speculated upon what reparations might look like in the children’s literature community. How could the dominant group make amends for the harm they’ve caused by excluding or misrepresenting so many children for so long? Decades after their unjust incarceration during World War II, Japanese Americans received a formal apology and financial compensation from the US government. Thirty years later, curators at the Dr. Seuss Museum apparently had no qualms installing a mural with a racist caricature of an Asian man. Could the persistence of such painful imagery (coupled with whitewashing by Hollywood) explain why so many Asian Pacific American kid lit creators choose to write about Whites? If two-thirds of African American authors and illustrators were making books about White children only, our community would be outraged—and I, for one, would be naming names. But I suspect that for Asian Pacific Americans, this is much more complex than “selling out” for personal gain.

It is difficult to measure the devastating legacy of living in a White supremacist society. Last month, while attending the launch of The Snowy Day stamp at the central branch of the Brooklyn Public Library, I found myself bristling at the celebratory mood of those around me. Ezra Jack Keats’ books were just about the only mirrors I had as a child in Canada, and I was thrilled to receive two pins—one for myself and one for my kindergarten teacher mother who introduced me to The Snowy Day when I was a student in her classroom forty years ago. Yet halfway through the ceremony I became acutely aware of the familiar silence around equity in children’s publishing. As Prof. Katharine Capshaw pointed out in her October 6 letter to the editor, the focus on Keats’ landmark book obscures the fact that “black writers and artists had been dreaming childhood in various incarnations, depicting the joys, pleasures and political investments of children since the Harlem Renaissance.” How much progress have we really made if fifty years after a White man wrote about a Black boy enjoying wintertime in Brooklyn, Black authors constitute just 3% of kid lit creators? The number of books about Blacks has skyrocketed over the past few years, but the number of books by Blacks has not. Power remains where it has always been in this country—in this industry—in this kid lit community: with Whites.

So how do we challenge the “innocent and harmless” image of those who dominate the kid lit community? Barbara Applebaum reminds us that, “racism is often perpetuated through well-intentioned white people” who can “reproduce and maintain racist practices even when, and especially when, they believe themselves to be morally good.” I am aware that there will be penalties for casting White women in the role of victimizer when they are accustomed to being recognized only as victims (the ultimate victim, even). But the sad truth is that my Black feminist perspective from the margins isn’t likely to sway those who occupy the center—and feel entitled to remain there. I nonetheless agree with the mandate put forward by Prof. Robin Bernstein: “It’s time to create language that values justice over innocence.” A group of rabbits is called a colony, and one could argue that White women have colonized the children’s literature community. It’s time to begin the process of decolonization. As Nikole Hannah-Jones explains, when it comes to racial inequality, “We have to challenge how we got here and make sure people understand that there are people, right now, who can be held accountable for it.”

Born in Canada, Zetta Elliott moved to the US in 1994 to pursue her PhD in American Studies at NYU. Her essays have appeared in The Huffington Post, School Library Journal, and Publishers Weekly. She is the author of over twenty-five books for young readers, including the award-winning picture book Bird. Her urban fantasy novel, Ship of Souls, was named a Booklist Top Ten Sci-fi/Fantasy Title for Youth; her latest YA novel, The Door at the Crossroads, was a finalist in the Speculative Fiction category of the 2017 Cybils Awards and her latest picture book, Melena’s Jubilee, won a 2017 Skipping Stone Award. Her own imprint, Rosetta Press, generates culturally relevant stories that center children who have been marginalized, misrepresented, and/or rendered invisible in traditional children’s literature. Elliott is an advocate for greater diversity and equity in publishing. She currently lives in Brooklyn. Learn more at zettaelliott.com.

There are a number of incorrect things in this article. I will try to address them today one by one. Let’s being with a major foundational error. The white population of the United States is not 61%, but 75%, according to the Census Bureau.

https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/2010_census/cb11-cn184.html

What is happening is that large numbers of people of Hispanic origin have come to self-identify as white. That makes sense because Hispanic is an ethnic classification, not a racial one. No amount of mental gymnastics could twist a white-skinned Argentinian-American and a dark-skinned Cuban-American into being the same race. Ethnicity and race are different things. This article from NPR explains more.

https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/06/16/321819185/on-the-census-who-checks-hispanic-who-checks-white-and-why

LikeLike

You haven’t addressed “a number of incorrect things” “one by one.” You’ve ‘splained while ignoring the main points of Zetta’s essay, which is exactly the sort of racist behavior that the essay covers. Thank you for providing an example of the kind of negativity that makes the climate in children’s literature so toxic for many.

LikeLike

Thanks, sis.

LikeLike

It is a shame when a raising of what John Adams called those stubborn things called facts is criticized as racist behavior. But, as Dr. Thomas Sowell says, “The word ‘racism’ is like ketchup. It can be put on practically anything – and demanding evidence makes you a ‘racist.'”

LikeLike

Thank you for this piece. I appreciate your approaching this through the lens of colonialism, because there’s such a long history of white authors speaking for people of color, and even if depictions are more authentic thanks to sensitivity readers, it’s still colonialism. Sensitivity readers making a tiny fraction of what the white author makes for the book written from the outsider’s perspective replicates the exclusion, exploitation and inequality of the colonial system.

LikeLike

I have to give Laura Atkins credit for that conclusion–I wanted to stick with my mafia analogy! I worried that by saying “colony,” White readers would automatically identify as victims once again–the 13 colonies defying the British. But hopefully they’ll see themselves in that other role–seizing, appropriating, decimating others…and I couldn’t agree more about sensitivity readers. The exploitation continues–with permission.

LikeLike

Great post. What I’ve been increasingly conscious of as I progress through the children’s lit community is that the ‘cult of nice’ holds us back from robust criticism in all sorts of areas. It’s good to be supportive and celebratory, but great work also needs real scrutiny and a willingness to challenge and i definitely notice that children’s lit scholarship is sometimes reluctant to provide that. So it’s no wonder we struggle to accept criticism on deeply rooted structural racism, because that is SUPER uncomfortable to hear about. I think we have to get used to being slightly less ‘nice’ and slightly more robust and challenging on a range of things, because making it part of how we operate makes it easier to swallow when it comes to the issues that really matter.

LikeLike

Rereading my comment, I feel like I am minimising the main issue in a ‘we are problematic in all sorts of ways’ way. Which – we ARE but the issue of race is the headline issue of this post for good reason and I do not want to handwave that.

LikeLike

Hi, Lucy! I didn’t read your comment as minimizing race at all. We talked about this happening at IRSCL last summer in Toronto; you can’t achieve real rigor without ruffling a few feathers. It’s a dangerous focus on “civility” (#keepYAkind!) that stifles dissent.

LikeLike

“But many of us know all too well that public displays of niceness often serve to camouflage or deflect attention away from actions and policies that are anything but kind.” This quote speaks to me about my role [White school librarian & blogger] in all of this. I really appreciate your continuing efforts to speak up and open our eyes to what’s happening in the children’s lit industry. Many White voices are speaking about the need for diversity, and in an industry dominated by White gatekeepers we are still mired in inequity, so we have to take a long look at our complicity. Perceived ideas about niceness contribute and keep the policies and procedures in place that have created these inequities. We may see ourselves as “harmless creatures operating with innocent intent,” but our actions and our lack of actions still have consequences. Thank you again for sharing your perspective. It’s a lot to think about and for myself, it’s an encouragement to do more to disrupt the current system.

LikeLike

Thanks for your thoughtful response, Crystal, and thanks for being one of those rare bloggers who’s willing to set policies that open the door a bit wider so more of us can come in!

LikeLike

It is of interest that a primary publisher of books by authors of color is Lee & Low. Cheryl Klein, an excellent and amazing editor was recently brought on as Executive Editor and the owner, and now part of Lee & Low, Stacy Whitman of Tu Books are both white females. Both have a deep commitment to publishing books by authors of color.

If there are going to be writers and illustrators of color, [for that matter if there are going to be editors and agents of color] there must be better writing and reading programs in the schools [ inner city/urban/suburban/rural] where there is an emphasis on methodology, mechanics and reading–everything from old dead white men to what is hot off the presses. There must be an understanding that this is a career if not a vocation. They must see authors of all kinds to understand that anyone, with grit, talent, perseverance, luck, good writing and a great story can write and publish.

Linda Sue Park [Newbery winner: A Single Shard] often says in order to write you need to read a thousand books. Good, no great creative writing takes place only when you know what rules to break, how and when to break them and use that knowledge to it’s fullest. Education is the key to broadening the possibilities.

LikeLike

I have a PhD; I have “grit, talent, perseverance” and have written numerous great stories. And I STILL can’t get most of my books published. If you’re talking about educating the White women running the publishing industry, I’m all for it! Most of them don’t have the cultural competence to assess work from writers of color and Indigenous writers. But there are lots of ways to tell stories; many of us come from oral cultures and don’t need to read hundreds of books UNLESS we’re trying to tell stories like other people. I would recommend you take a look at Stamped from the Beginning by Ibram Kendi: https://theundefeated.com/features/ibram-kendi-leading-scholar-of-racism-says-education-and-love-are-not-the-answer/

LikeLike

Yes, I am talking about white women running publishing, managed by white men 🙂 And I agree that as gatekeepers they are not ideal, not even close. I have challenged many an editor/agent/publisher to explain why there are so few people of color, indigenous writers on the ‘gatekeeping’ side of the industry and I have yet to receive a substantial answer, except to say that they are not coming through the pipeline.

And yes, I come from an oral tradition of storytelling- the Irish, with a dear friend who is a champion of the mideastern tradition of story telling, a very different sort of story methodology. But the stark truth is, if you wish to publish so that children can see and hear a different life/culture/tradition, at this time, you need to work the system, because right now, that is what is out there. I firmly believe and acknowledge you can only accomplish real change from the inside. I will look up Ibram Kendi. Thank you for the reference.

LikeLike

Hi Teresa, in your first response, you stated your belief that education is key in getting marginalized writers in print. I agree, but probably not in the way you mean. Schools are where we develop our social networks and it’s these networks that often help us find employment. Publishing, like most any industry, is filled by people who look like each other because they come from the same network. For someone with a stellar education who didn’t attend the universities from which publishers typically hire will be a challenge. And then, there’s the education of those who attend all White schools, live in all White communities and will never be able to claim “but I have a black friend”. The burden shouldn’t doesn’t fall upon the marginalized.

I do think that self publishing is becoming a viable alternative for those marginalized from traditional publishing houses and it will be interesting to see how innovative platforms and technologies do change the traditional paradigm.

I think Zetta hits so many undeniable points on why exclusion continues. Excuses for them will not move us forward.

LikeLike

You are thinking in terms of a system. I’m thinking of education in terms of opening the mind to possibilities. Anyone who has broken out of a system, and there are many, knows that the possibilities are what count. And I don’t know what the key is to getting current marginalized voices in print. God knows, I have worked on it with various organizations. I think the possibilities in the future are great!

Publishing, from my experience is not quite as linear as you may think, but then again, lol, if you read some of the popular dystopian books you will know that some authors and editors, who are white, may have stellar educations but not the brains to use them.

And yes, self publishing has moved from vanity publishing to more mainstream, especially with the advent of platforms like Goodreads, Net Galley and BookBub, not to mention the Amazon powerhouse!

I think the burden is on all of us–yeah, I know, not a popular statement. What I think about the exclusion issue is not relevant…that is for each person to decide, deal with, make better. No excuses on any side. But, yes, I am an optimist, I have hope.

LikeLike

Your comment only makes sense if you think there aren’t already people of color with the talent and the craft to publish. The point of this article is that the craft and talent exists, but white gatekeepers refuse to recognize it and are afraid to champion it.

LikeLike

I know there is talent in the marginalized voices and I know they can write! I make no excuses for the gatekeepers, I am not one of them and have no reason to protect them. And frankly, not all of them are white, especially in the children’s lit world. But I know they are also in business. And while they all say they want diversity, one must wonder if it is the ‘bottom line’ that is a detriment and a distraction.

For a number of years The Children’s Book Council has had a diversity committee. http://www.cbcbooks.org/about/cbc-diversity-committee/

LikeLike

Teresa, have you gone over to Zetta’s blog to read her conversation with Laura Atkins? I suggest you do. Just read it and ponder it; try just listening.

LikeLike

[…] Kelly Starlings Lyon: How Do Women Use Art As Resistance? Zetta Elliott: Nice Is Not Enough […]

LikeLike

[…] Elliott: Nice Is Not Enough Traci Sorrell: Why Do You Speak […]

LikeLike

[…] Essays in this series: Kelly Starlings Lyon: How Do Women Use Art As Resistance? Zetta Elliott: Nice Is Not Enough Traci Sorell: Why Do You Speak […]

LikeLike

Thank you for the post. As an illustrator I had a very lengthy and heated debate on an artist forum about the “our voices” movement. For some reason no matter how it was explained the white males in the conversation could not wrap their heads around two things. 1. They predominated the industry as illustrators even for works about people of color and that is unbalanced borderline appropriation. 2. That a book about a person of color could be more authentic in so many more ways coming from a person of similar background. It was like they were trying to convince us to obvious contrary evidence that this is not a good direction to move into for one simple unspoken reason economics. They did not like the idea of losing a potential book deal simply because of the color of their skin and their racial background. It was ok for it to benefit them but not hinder them lol I was even called racist in a backhanded sort of way during the discussion.

LikeLike

[…] Starlings Lyon: How Do Women Use Art As Resistance? Zetta Elliott: Nice Is Not Enough Traci Sorell: Why Do You Speak […]

LikeLike

[…] Starlings Lyon: How Do Women Use Art As Resistance? Zetta Elliott: Nice Is Not Enough Traci Sorell: Why Do You Speak Out? Justina Ireland: There is A Minefield and You Will Become a […]

LikeLike

[…] Starlings Lyon: How Do Women Use Art As Resistance? Zetta Elliott: Nice Is Not Enough Traci Sorell: Why Do You Speak Out? Justina Ireland: There is A Minefield and You Will Become a […]

LikeLike

[…] Starlings Lyon: How Do Women Use Art As Resistance? Zetta Elliott: Nice Is Not Enough Traci Sorell: Why Do You Speak Out? Justina Ireland: There is A Minefield and You Will Become a […]

LikeLike